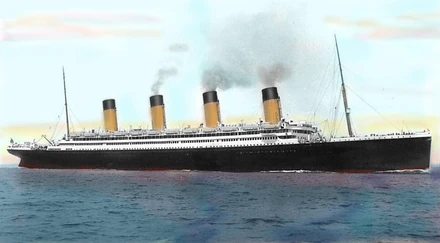

RMS Olympic is a largest ocean liner at that time in 1911.

Bio[]

RMS Olympic was a transatlantic ocean liner, the lead ship of the White Star Line's trio of Olympic-class liners. Unlike her younger sister ships, the Olympic enjoyed a long and illustrious career, spanning 24 years from 1911 to 1935. This included service as a troopship during the First World War, which gained her the nickname "Old Reliable". Olympic returned to civilian service after the war and served successfully as an ocean liner throughout the 1920s and into the first half of the 1930s, although increased competition, and the slump in trade during the Great Depression after 1930, made her operation increasingly unprofitable.

She was the largest ocean liner in the world for two periods during 1911–13, interrupted only by the brief tenure of the slightly larger Titanic (which had the same dimensions but higher gross tonnage due to revised interior configurations), and then outsized by the SS Imperator. Olympic also retained the title of the largest British-built liner until the RMS Queen Mary was launched in 1934, interrupted only by the short careers of her slightly larger sister ships.

By contrast with Olympic, the other ships in the class, Titanic and Britannic, did not have long service lives. On the night of 14/15 April 1912, Titanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sank, claiming 1,500 lives; Britannic struck a mine and sank in the Kea Channel in the Mediterranean on 21 November 1916, killing 30 people.

Built in Belfast, Ireland, the RMS Olympic was the first of the three Olympic-class ocean liners – the others were the RMS Titanic and the HMHS Britannic. They were by far the largest vessels of the British shipping company White Star Line's fleet, which comprised 29 steamers and tenders in 1912. The three ships had their genesis in a discussion in mid-1907 between the White Star Line's chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, and the American financier J. Pierpont Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line's parent corporation, the International Mercantile Marine Co. The White Star Line faced a growing challenge from its main rivals Cunard, which had just launched Lusitania and Mauretania – the fastest passenger ships then in service – and the German lines Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd.

Ismay preferred to compete on size rather than speed and proposed to

commission a new class of liners that would be bigger than anything that

had gone before as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury. The company sought an upgrade in their fleet primarily in response to the Cunard giants but also to replace their largest and now outclassed ships from 1890, the SS Teutonic and SS Majestic. The former was replaced by Olympic while Majestic was replaced by Titanic. Majestic would be brought back into her old spot on White Star's New York service after Titanic's loss.The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilders Harland and Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867. Harland and Wolff were given a great deal of latitude in designing ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn into a ship design. Cost considerations were relatively low on the agenda and Harland and Wolff was authorised to spend what it needed on the ships, plus a five percent profit margin. In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million for the first two ships was agreed plus "extras to contract" and the usual five percent fee.

Olympic's first major mishap occurred on her fifth voyage on 20 September 1911, when she collided with a British warship, HMS Hawke off the Isle of Wight. The collision took place as Olympic and Hawke were running parallel to each other through the Solent. As Olympic turned to starboard, the wide radius of her turn took the commander of the Hawke by surprise, and he was unable to take sufficient avoiding action. The Hawke's bow, which had been designed to sink ships by ramming them, collided with Olympic's starboard side near the stern, tearing two large holes in Olympic's hull, below and above the waterline respectively, resulting in the flooding of two of her watertight compartments and a twisted propeller shaft. HMS Hawke suffered severe damage to her bow and nearly capsized. Despite this, Olympic was able to return to Southampton under her own power, and no-one was seriously injured or killed.

Captain Edward Smith was still in command of Olympic at the time of the incident. One crew member, Violet Jessop, survived not only the collision with the Hawke but also the later sinking of Titanic and the 1916 sinking of Britannic, the third ship of the class. At the subsequent inquiry the Royal Navy blamed Olympic for the incident, alleging that her large displacement generated a suction that pulled Hawke into her side. The Hawke incident was a financial disaster for Olympic's operator. A legal argument ensued which decided that the blame for the incident lay with Olympic,

and although the ship was technically under the control of the pilot,

the White Star Line was faced with large legal bills and the cost of repairing the ship, and keeping her out of revenue service made matters worse. However, the fact that Olympic endured such a serious collision and stayed afloat, appeared to vindicate the design of the Olympic-class liners and reinforced their "unsinkable" reputation.

It took two weeks for the damage to Olympic to be patched up sufficiently to allow her to return to Belfast for permanent repairs, which took just over six weeks to complete. To speed up the repairs, Harland and Wolff was forced to delay Titanic's completion in order to use her propeller shaft for Olympic. By 29 November she was back in service, however in February 1912, Olympic suffered another setback when she lost a propeller blade on an eastbound voyage from New York, and once again returned to her builder for repairs. To get her back to service as soon as possible, Harland & Wolff again had to pull resources from Titanic, delaying her maiden voyage from 20 March 1912 to 10 April 1912.

In August 1914 World War I began. Olympic initially remained in commercial service under Captain Herbert James Haddock. As a wartime measure, Olympic was painted in a grey colour scheme, portholes were blocked, and lights on deck were turned off to make the ship less visible. The schedule was hastily altered to terminate at Liverpool rather than Southampton, and this was later altered again to Glasgow. The first few wartime voyages were packed with Americans trapped in Europe, eager to return home, although the eastbound journeys carried few passengers. By mid-October, bookings had fallen sharply as the threat from German U-boats became increasingly serious, and White Star Line decided to withdraw Olympic from commercial service. On 21 October 1914, she left New York for Glasgow on her last commercial voyage of the war, though carrying only 153 passengers.

Following Olympic's return to Britain, the White Star Line intended to lay her up in Belfast until the war was over, but in May 1915 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty, to be used as a troop transport, along with the Cunard liners Mauretania and Aquitania.

The Admiralty had initially been reluctant to use large ocean liners as troop transports because of their vulnerability to enemy attack,

however a shortage of ships gave them little choice. At the same time, Olympic's other sister ship Britannic,

which had not yet been completed, was requisitioned as a hospital ship. In that role she would strike a mine and sink the following year. Stripped of her peacetime fittings, and armed with 12-pounders and 4.7-inch guns, Olympic was converted to a troopship, with the capacity to transport up to 6,000 troops. On 24 September 1915 the newly designated HMT (Hired Military Transport) 2810, now under the command of Bertram Fox Hayes left Liverpool carrying 6,000 soldiers to Mudros, Greece for the Gallipoli Campaign. On 1 October she sighted lifeboats from the French ship Provincia which had been sunk by a U-boat that morning off Cape Matapan

and picked up 34 survivors. Hayes was heavily criticised for this

action by the British Admiralty, who accused him of putting the ship in danger by stopping it in waters where enemy U-boats were active. The ship's speed was considered to be its best defence against U-boat attack, and such a large ship stopped would have made an unmissable target. However the French Vice-Admiral Louis Dartige du Fournet took a different view, and awarded Hayes with the Gold Medal of Honour. Olympic made several more trooping journeys to the Mediterranean until early 1916, when the Gallipoli Campaign was abandoned.

Many years later, The Olympic was out of her retirement and ready to sail once again.

Crew of the Ship[]

- Russell Ferguson (Captain)

- Zoe Trent (First Mate)

- Pepper Clark (Second Mate)

- Minka Mark (Third Mate)

- Vinnie Terrio (Forth Mate)

- Sunil Nevla (Fifth Mate)

- Penny Ling (Sixth Mate)

- Digby

- Captain Cuddles

- Steve the Cobra

- Gail Trent

- Mitzi

- Basil Featherstone

- Delilah Barnsley

- L-Zard's crew

- Buttercream Sunday

- Sugar Sprinkles

- Nutmeg Dash

- Madame Pom LeBlanc

- Parker Waddleton

- Cashmere and Velvet Biskit

Trivia[]

- The RMS Olympic was saved from scrap and rebuild by SpongeBob SquarePants and his pals, thanks to The SquarePants Master Ship Builders.

- Princess Yuna and her friends will see the RMS Olympic in Rise of the Maximals Part 1.

- The RMS Olympic will make her first ever appearance in Rise of the Maximals Part 1.